Akihisa Yamamoto: Born in 1975. Joined the family business after graduating from university. As part of Yamamoto Metal Works, the only producer of handcrafted Japanese mirrors, sacred mirrors, and magic mirrors in Japan, he is involved in the production of mirrors for Shinto shrines used as sacred hosts or offerings, the restoration of mirrors in museum collections, and more.

First generation: Ishimatsu Yamamoto

Second generation: Shinichi Yamamoto

Third generation: Shinji Yamamoto (Ouryu)

Fourth generation: Fujio Yamamoto (pictured on left)

Fifth generation: Akihisa Yamamoto (pictured on right)

– A family of mirror makers

The last mirror maker—this phrase is appearing more often in introductions of Akihisa Yamamoto, the fifth generation of Yamamoto Metal Works, the only producer of handcrafted Japanese mirrors. As his father Fujio is still an active mirror maker the moniker is not exactly accurate, but they are rare nonetheless. The family began its business in 1866 at the end of the Edo period, when Japanese mirrors were still an indispensable part of daily life. Since then, the family of mirror makers has continued making mirrors by hand through 151 years of upheaval and change.

Once a bronze mirror is cast, it is ground and polished repeatedly. Much of a mirror maker’s work is done while sitting cross-legged.

Yamamoto Metal Works was founded in 1866, in the final years of the Edo period. Ishimatsu Yamamoto, the first generation, trained at the Kanamori family’s renowned mirror studio in Kyoto before striking out on his own. Armed with the traditional techniques of Kyoto, he joined the dozens of other mirror makers that were in Kyoto at the time.

It was a time when Japanese mirrors were still an indispensable part of everyday life. In addition to the creation of new mirrors, polishing old, cloudy mirrors was a significant portion of a mirror maker’s work. Some craftsmen specialized in visiting households to polish old mirrors, an indication of the close relationship mirrors had with daily life.

But partway through the Meiji era (1868 – 1912), more and more mirror makers began going out of business due to the rapid spread of glass mirror. Renowned studios such as the Kanamori family and the Ao family known for providing mirrors to the Imperial palace shut their doors, and when the Showa era (1926 – 1989) arrived the Yamamoto family was the only remaining mirror maker in the city of Kyoto. Shinichi, son of the founder Ishimatsu, took over as the second generation and had become known nationwide as a mirror maker of Kyoto.

Shinji (Ouryu) joined the family business as the third generation in 1934. The Yamamoto family primarily produced sacred mirrors to be used as hosts for the gods of Shinto shrines and would singlehandedly meet the demand for sacred mirrors for shrines dedicated to the war dead, built around the country during the height of state-sponsored Shintoism. Amid a hectic schedule, Shinji and his father created mirrors of a wide variety of sizes and designs. The refined techniques that would later make Shinji the first mirror maker named an Intangible Cultural Property were likely developed during this time.

Polishing with whetstones, magnolia charcoal, and paulownia charcoal gradually changes rough metal into a mirror surface.

– Christian magic mirrors

Shinji, the third generation, found the method to create Christian magic mirrors in 1974. It was the year before the birth of Akihisa, who would later become the fifth generation.

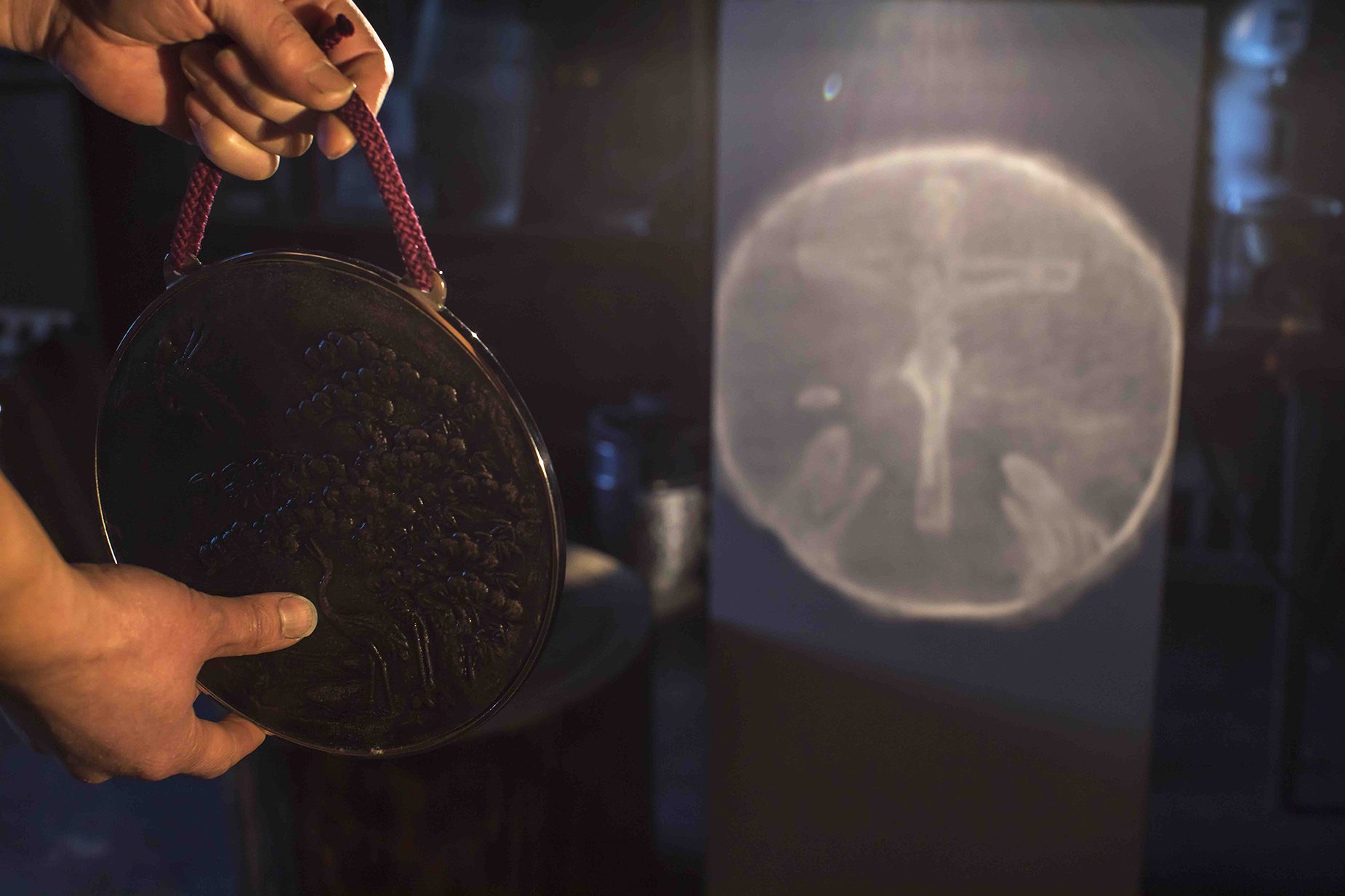

The term “magic mirror” refers to a mirror that projects the design applied to its back in its reflected light. In ancient China, mirrors with such properties were highly valued, known as touguangjing (“light-penetration mirrors”). In Japan, they begin appearing in historical documents around the middle of the Edo period. In particular, the Christian magic mirrors used by Christians who endured persecution for their forbidden faith during the Edo period are well known. They are normal mirrors at first glance, but in a strong light they project images such as Mary or Jesus in the reflection, making them ideal everyday items that could be used for hidden worship.

While there were surviving examples of magic mirrors, how they work remained a mystery and they were the focus of research by many scholars. Edward S. Morse and John Perry, educators brought to Japan by the Meiji government, introduced the mirrors’ mysterious appeal to their home countries. The Japanese name for the magic mirrors is a direct translation of the English term “magic mirror” used in Western academic journals of the time.

When metal mirrors wear down from repeated grinding and polishing, they can sometimes project the design on the back. Far before the name “magic mirror” was coined, old, re-polished mirrors could sometimes display the magic mirror phenomenon. These chance occurrences were often seen as divine in nature, but there must have been mirror makers who grasped the principle behind it to create magic mirrors intentionally. The Christian magic mirrors are one example of obviously intentional creations.

“It was just natural for me to take over the family business. I think my father and grandfather must have done a good job leading me along that path.”

– Akihisa, the fifth generation

Unlike many Kyoto craftsmen, Akihisa grew up without any involvement in the family business. The home and studio were separate, and his father didn’t talk about work at home.

“Until I helped out on a part-time basis when I was in college, I didn’t even know what kind of work my father and grandfather did. I wasn’t interested, either.”

He began helping with his father’s work to earn some spending money after his father offered him 50 yen more than his previous part-time job, but that gradually led to genuine enjoyment.

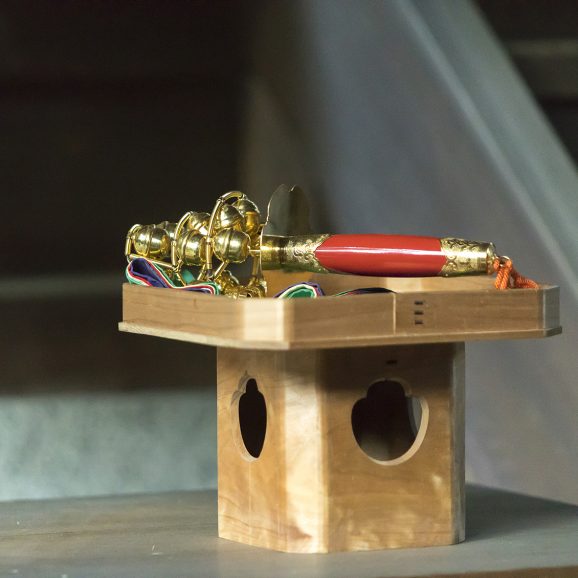

“The work I was given was to make cast metal implements used in Buddhist worship. I was repeating the same motions over and over, but it was immensely enjoyable. I guess it just agreed with me. The craftsmen were all kind, and it was a comfortable environment. Before I realized it, I had joined the family business.”

Five years after he began working in the family business, his grandfather started him on learning to make mirrors. His training to become the fifth generation of Yamamoto Metal Works mirror makers began.

“Many people think training to become a craftsman is a strict, grueling process, but it wasn’t like that at all in my case. We were grandfather and grandson, after all. If I had a question he’d always answer, and he never got angry with me. My grandfather, great-uncle, and father all made mirrors, so it helped that I could draw on skills and knowledge from each of them. I think I got a very fortunate start as a craftsman.”

His great-uncle Hachiro was a particularly big influence on Akihisa. Hachiro was both younger brother to Shinji, the third generation, and a craftsman who had supported his brother for years. Hachiro worked closely with Akihisa to teach him, and Shinji provided instruction on the key points. Akihisa’s father, Fujio, watched over the training.

Through the distinct teaching styles of the three mirror makers, Akihisa absorbed knowledge and skills quickly.

(left) Over 200 different carving tools are used to form designs in the sand mold for the back of the mirror. (right) There are many metal files of differing roughness used to grind a mirror after it is cast.

“My grandfather and great-uncle were old school craftsmen who thought if you do good work, that’s all you need. They were incapable of cutting corners, kept at it until they were satisfied, and would turn away work they didn’t like. I learned the craftsman’s spirit from them. On the other hand, from my father I learned that while you’re a craftsman, you need to think about the business side as well. There are things you can’t ignore in your work, like expenses and deadlines.”

– The future of mirror makers

“Just blindly continuing to hand-craft mirrors is meaningless. No matter how traditional it is, there’s no point if there is no demand for it. That’s especially true in this day and age, where Japanese mirrors aren’t necessary for everyday life. We need to find a way to use the techniques of handcrafting to give back to society,” says Akihisa. He says he thinks about the meaning of continuing with handcrafting and the meaning of working as a craftsman just as much as he works on improving his skills.

A steel tool called “sen” with handles on both sides is used to grind the mirror’s surface.

“I’m often asked why we don’t make the mirrors with machines, but that’s because the techniques of handcrafting are still necessary. If we were only making new mirrors we might be able to do that with machines, but restoration and refinishing is an unavoidable part of working with Japanese mirrors. You can’t restore an old mirror without the skill to make a mirror from scratch by hand. But if my cost is considered too high, that means mirror makers aren’t needed in modern society. It’s a hassle, but to keep working as a mirror maker in a time when Japanese mirrors aren’t necessary for everyday life, I have to keep thinking about things like this.”

A mirror decorated with sea creatures and grape vines, known as “kaiju budo kyo.” Many were made in China during the Sui and Tang dynasties and brought to Japan. Yamamoto Metal Works produces replicas of items from museum collections as well.

Once handicraft skills are lost to mechanization, it is difficult to relearn them.

Akihisa’s statement that handicrafts are his reason for existence shows the pride of the fifth generation of mirror makers.

“No matter how valuable skills might be, if they don’t make sense as work they’re meaningless. I have to keep trying to get the word out about the detailed, handcrafted work that goes into making mirrors. I think that’s my responsibility as a craftsman in the modern age, and that’s what differentiates me from my grandfather and the generations before him.”

The sand mold for a Christian magic mirror. A sand mold can only be used for one cast, so it is created by pressing with carving tools each time.

SPECIAL

TEXT BY YUJI YONEHARA

PHOTOGRAPHS BY MITSUYUKI NAKAJIMA

17.08.25 FRI 19:02